Vulvic Thinking

The vulva is a fraught

and evolving site that is calling out for dedicated study by feminists. We need

to analyse, broaden, and deepen cultural representations and discussions around

vulvas. The vulva is enjoying a zeitgeist. Fur cup, yoni, cunt, front bottom,

hoo-ha, pussy, va-jay-jay, camel toe,

muff, map of Tassie, vagina. After hearing the sound recording of the now President of the Unites

States advising men to ‘grab em by the pussy’

women rose up in fury to march against gendered violence as well as against the

President himself. Global newscasts showed crowds in cities across the world dotted

with homemade signs featuring the word vulva and images of vulvas (most were

pink, an omission of note: see

https://amydame.ca/2017/05/09/not-all-pussies-are-pink-not-all-women-have-pussies/).

Alongside my sisterly anger the nerd in me felt happy that, at last, people were using correct

terminology: instead of ‘vagina’ we were hearing ‘vulva’: the proper general descriptor

for labia minora and majora, the external parts of the clitoris, the clitoral

hood, and the opening to the vagina.

|

| Photo by roya ann miller on Unsplash |

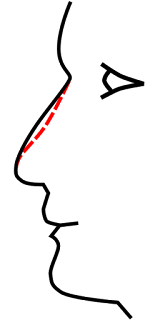

The current vulvic zeitgeist—unlike the legendary second wave

feminist consciousness raising groups that encouraged women to use mirrors to

self-examine and demystify their genitals—is occurring alongside sometimes

overwhelming cultural and social pressures for women to work on their bodies

and femininities through exercise, diet, grooming and cosmetic surgery. The

mainstreaming of pornography and the ubiquitous use of Photoshop have led to

dissemination of an homogenous 'ideal-looking' vulva that is promoted by

television programmes such as Embarrassing Bodies, by some

gynaecologists, and certainly by cosmetic surgeons. The term

‘designer vagina’, otherwise known as female genital cosmetic surgery, covers a

range of cosmetic surgery procedures including vaginal tightening, hymen repair

or reconstruction, labia minora reshaping or minimizing, labia majora

augmentation or reduction, clitoral hood removal, reduction, or rebuilding, and

‘G-spot’ enhancement. In parallel with rising numbers

of requests for ‘designer vaginas’ legislation against female genital

mutilation was introduced in the UK in 2013 (an irony that has not gone

unnoticed 1). There are

concurrent cultural reactions to this as academics, artists

[http://www.greatwallofvagina.co.uk/about], activists and documentary makers [https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/video/2016/sep/23/vagina-dispatches-part-one-what-vulvas-look-like]

endeavour to disseminate a more representational range of healthy vulvas.

There are many ways we could expand the frames through which we

examine these intricate and multifaceted body parts, for example by focusing on

the sensorium, the emotions, and everyday embodiments as well as the more

obvious frames of pleasure, desire, and oppression. Ethnographies of vulvas are

urgently required! How might we critically and creatively engage with vulvic

discourses as well as with vulvas themselves? Perhaps what is required is a

whole new mode of thinking: vulvic thinking. For Luce Irigaray, vulval lips are multiple

and relational: they are visual but are also doing and becoming, and are thus able to express in ways that destabilize

‘truth’ and grand narratives. Labia is the plural of labium, a Latin-derived

term meaning lip, so its roots are in the plural and are strongly linked to

speaking, doing, communicating. How might feminist scholars communicate better

with and about vulvas? How might we surf the current wave of vulval visibility?

How might we use it to destabilise and interrogate? How might we research and think

about, with, and even through our

vulvas?

Meredith Jones is a Reader in Gender and Media Studies at Brunel University London. She is a feminist scholar specialising in theories of the body and is one of the pioneers of social and cultural research around cosmetic surgery. Her books and articles, especially ‘Skintight: An Anatomy of Cosmetic Surgery’ (Berg, 2008) in the area are widely cited. Meredith is currently writing (with David Bell and Ruth Holliday) a book about cosmetic surgery tourism (based on data collected as part of the project Sun, Sea, Sand and Silicone) and a monograph tentatively titled ‘Velvet Gloves: A Cultural Anatomy of the Vulva.

1 The Nuffield Council on Bioethics’ 2017 report Cosmetic procedures: ethical issues notes 'a concerning lack of clarity as to whether procedures offered as FGCS fall within the ambit of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003' and recommend 'that the Home Office should clarify the circumstances in which procedures offered as ‘FGCS’ do, or do not, fall within the ambit of the FGM Act, in the light of ongoing concerns as to their legality.'↩

1 The Nuffield Council on Bioethics’ 2017 report Cosmetic procedures: ethical issues notes 'a concerning lack of clarity as to whether procedures offered as FGCS fall within the ambit of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003' and recommend 'that the Home Office should clarify the circumstances in which procedures offered as ‘FGCS’ do, or do not, fall within the ambit of the FGM Act, in the light of ongoing concerns as to their legality.'↩

Comments

Post a Comment